The story of Egypt has been a vital component in explaining early world history. The stories continue to capture the imagination. Much of what we now know was captured through early writings and documentations made on what is called papyrus. Think of it as ancient paper. It just so happens the largest collection of Papyri in North America is right in our area. Walk through the U of M’s central campus Diag, in the doors to one of the school’s most recognizable buildings and, as 89.1 WEMU’s Jorge Avellan reports, you’ll discover a world that has been “Hidden in Plain Sight.”

It takes you less than 60 seconds to get up to the 8th floor of the Hatcher Graduate Library. When you walk out of the elevator is looks like every other floor--that is, until you enter room 807. It’s like being transported back in time. It’s the home of the Papyrology Collection for the university.

"You’ll find everything from ancient literature for instance here, a fragment of Homer’s Iliad Book 18 to Christian description pages from an ancient codex book that contained Letters of St. Paul."

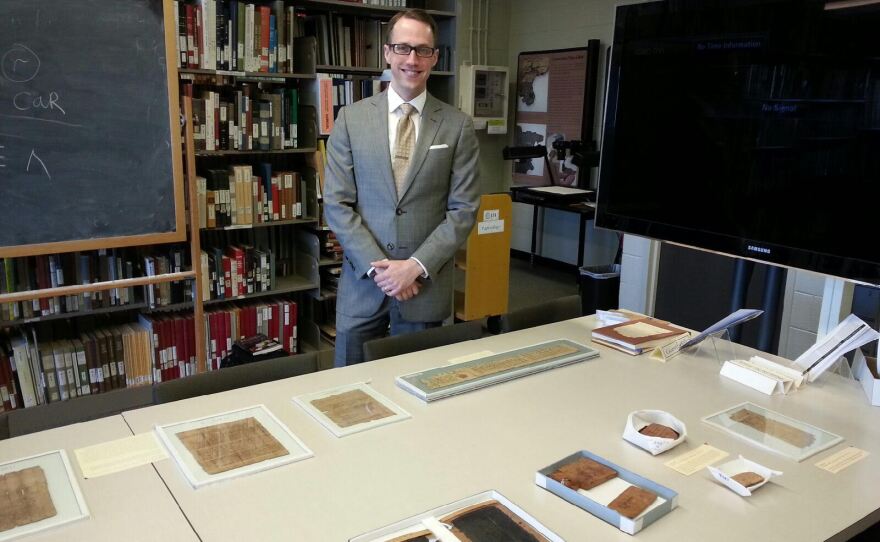

Brendan Haug is the archivist for the collection. He’s laid out papyri over several tables in the room’s main gathering area. Some are torn into small pieces about the size of a post-it, while others remind you of an 8x10 sheet of paper. The dark and light colored pieces of papyri are protected by glass frames.

"This object on the left is two of 30 leaves we possess from an ancient book that contained most of the Letters of St. Paul of canonical text of the New Testament. They were originally dated somewhere between the 2nd and the 3rd Century. These are more likely to be of the 4th Century AD. So they are either the earliest or among the earliest surviving copies in the world of epistles of St. Paul. These are extremely well known among the scholars of the New Testament," added Haug.

Haug says they estimate the entire collection to be worth more than $100 million. The title for the oldest piece in the collection is a text-fragment from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. It dates to about the 10th or 11th Century B.C.

There are more personal items in the collection as well, like a letter from a young Greco—Egyptian recruit who joined the Roman fleet and sent letters home to his mother. But, Haug explains, it is highly unlikely the young soldier wrote it himself.

"So the average person in the ancient world, even if they have to pay taxes and keep documents is still going to be illiterate. So, any village will have one or more scribes who are responsible for not only keeping records on behalf of the state, but, they will also be the folks that you can go to dictate a private letter if you want to write a private letter to another family member. The scribe will take dictation for you. They will write contracts for you, if you’re selling or leasing something," said Haug.

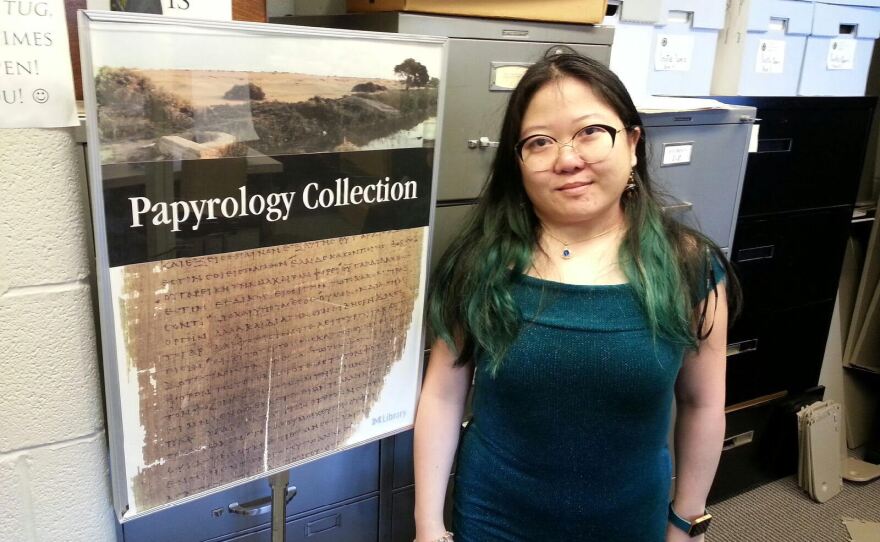

Monica Tsuneishi is the manager of the roughly 18,000 piece papyrology collection at the University of Michigan. She says, about 5,000 pieces have never been studied or translated.

"These are the voices of people that had been long dead for hundreds and hundreds of years, but their voices are still here," said Tsuneishi.

It was U of M Latin professor Francis W. Kelsey that heard the calling of those voices. He led archeological expeditions in the early part of the 1900’s. Through his excavation work, the university began acquiring its papyrology collection in 1920. But, that’s only part of the process. Once collected, Tsuneishi explains it is a rigorous process to translate these materials.

"Some people will work on scraps of papyri that are only maybe a couple of inches big. And it’s harder when your fragments are smaller because there is less content for it. But after years of learning the particular language, and years of going over papyri that maybe had already been read over before, then you can start comparing and seeing things. It still takes people months, even years before they get to the actual publication stage for the papyrus," added Tsuneishi.

Once in the school’s possession, preserving these ancient texts is a priority. So, we return to our visit with archivist Brendan Haug.

"The environmental room here dates back to the 1990’s and its designed to keep the material stable," said Haug.

I get a chill as I walk into the midsize dark room with overhead lighting. The temperature is usually kept between 60 and 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Dozens and dozens of archival boxes are stored like books in the stacks of a library. Haug grabs one of the boxes and opens it.

Brendan: That’s a fragment that bares a little bit of 8th Century AD Greek and heavily abbreviated accounting text. With the characteristic Greek hands of the 8th Century and then you turn it over this way and it also has been used to write a letter in Arabic, fragmentary. It begins at the top, In the name of God, the passionate and the merciful, as all Arabic documents will start…And begins the letter from someone named Karim and then breaks off.

Jorge: So, this was recycled paper in a way?

Brendan: Exactly, you’ll find a lot of recycling in the ancient world. Everything from using the blank side of something, after its front outlives its usefulness, to the point that documents, which had been thrown away would often been recycled as a sort of papyrus-mache, like papier-mâché and made intro hard shell to wrap mummies.

Anywhere you go in Washtenaw County, you can find the most advanced technologies and modern facilities. But, a look at a world that existed thousands of years ago isn’t all that far away, either. In fact, it’s easily accessible, right in Ann Arbor, “Hidden in Plain Sight.”

Visit the Papyrology Collection: Appointments are recommended

Hatcher Graduate Library, Room 807

913 S. University Avenue

Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1190

Contacts:

Brendan Haug : bjhaug@umich.edu

Monica Tsuneishi : monicats@umich.edu

(734) 764-9369

Non-commercial, fact based reporting is made possible by your financial support. Make your donation to WEMU today to keep your community NPR station thriving.

Like 89.1 WEMU on Facebook and follow us on Twitter

— Jorge Avellan is a reporter for 89.1 WEMU News. Contact him at 734.487.3363 or email him javellan@emich.edu